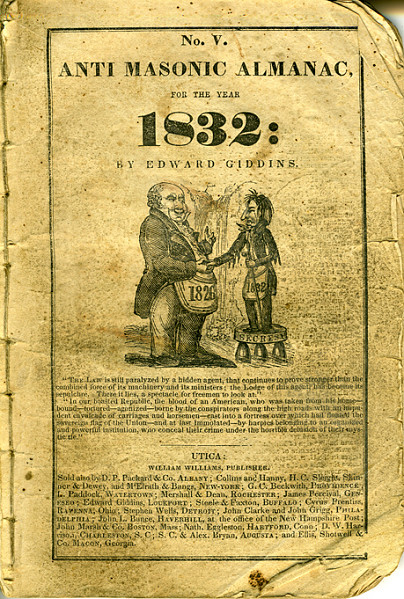

In the vast history of American politics and its political parties, the Anti‑Masonic Party was an American political organization which had its rise after the mysterious disappearance, in 1826, of William Morgan, a Freemason of Batavia, New York, who had become dissatisfied with the Order and planned to publish its secrets. It is the only political party that emerged as the result of one isolated incident in the history of the United States, rose quickly and powerfully due to the political and social situations of the time, and then died quietly, possibly holding the record of a political party with the shortest life in the history of American politics.

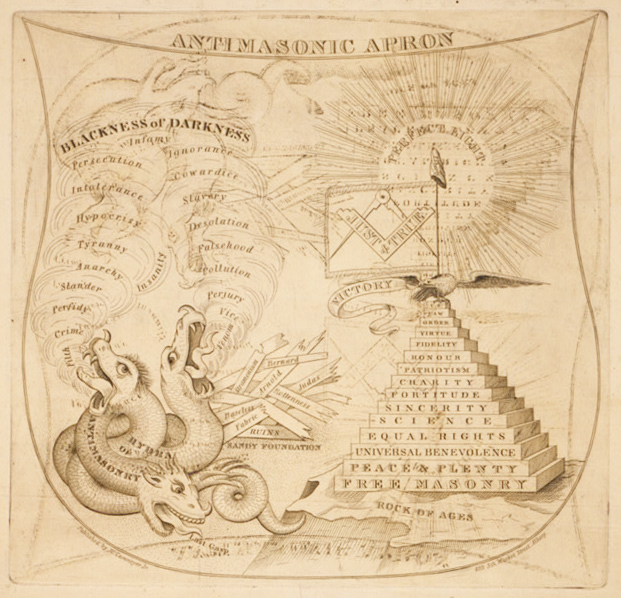

To understand the nature of the political movement and its effects, one must first understand the nature of the Fraternity. There is no Society so widely known, and yet really so little known, as that of the Free and Accepted Masons. Freemasonry is an ancient and honorable 3,000 year old fraternity. So high was its eminence that to its credit – in every age – Monarchs themselves have been promoters of the institution and the art, that they have not thought it derogatory from their dignity to exchange the scepter of power for the trowel that spreads the cement of brotherly love, patronizing its mysteries and joining in its assemblies without regard for race, creed or color. It has become the oldest, largest and most widely known fraternal organization in the world and the prototype of most modern fraternal societies and service organizations.

Masonry began as an Art founded on the principles of Geometry. Every Mason was required to take a solemn oath of secrecy, whereby the secrets of their trade could not be divulged to any other person outside of the Craft.

However, through the centuries, Masonry embraced a wider range, “having a more noble object in view – namely, the cultivation and improvement of the human mind.”1 With the transition of the Craft into a society of intellectuals, the secrets of the Order changed from the trade secrets of the stone mason to secrets guarding the Ceremonies of Initiation; however, nowhere in the Ceremonies of Initiation does a member’s vow require him to lift his hand in anger or warning against an errant brother who betrays his trust.

William Morgan was a man of disreputable character, a vagrant, harassed by debt; his time was mostly spent in bar rooms, and without corroborative evidence no credence would be given to any statement he made. Failing as a brewer in Canada, he moved to Rochester as a stone mason, and there he went to Batavia in 1823. An anti‑Masonic letter to President John Quincy Adams says:

“He was a hard drinker, and his nights and sometimes his days also were spent in tippling houses, while occasionally, to the still greater neglect of his family, he joined in the drunken carousals of the vilest and most worthless men, and his disposition was envious, malicious, and vindictive.”2

Having been a member of the Fraternity in Canada, he attempted to become a member of Wells Lodge, #282 in Batavia; however, owing to his dissolute character, his petition was revoked and was consequently denied admission. Having tried petitioning several times without effect, this tendency began to irritate him considerably and, being unprincipled enough to do anything of a disreputable nature, he, with his associate, David Miller (a newspaper publisher of comparable character), originated the scheme of publishing the Fraternity’s secrets for the purpose of revenge and untold wealth.

When his purposes became known to the members of the Fraternity, Morgan was subjected to frequent annoyances by being continually arrested on petty charges of which he was guilty, until a plan was set out by a few misled Masons to obtain possession of the manuscript at all costs or hazards.

On the night of 8 September 1826, a party of forty persons assembled with the objective of sacking Miller’s office for the manuscript; but the better class of citizens, as well as Miller’s friends, rallied to his support, and no such rash measures were taken; however, two nights later the office was discovered to be on fire, but the flames were quickly extinguished, with the arsonists escaping. On 13 September after several attempts by the Fraternity to suppress the publication and retrieve the manuscript, it was believed, at that time, that he was seized and secretly conveyed to Fort Niagra, where he disappeared. Although there is no positive proof that Morgan had been carried away, and though his ultimate fate was never known, it was generally believed at the time that he had been drowned at Niagra by the Masonic Fraternity because of his intended plot of revenge. This story aroused the most intense excitement, and it was upon this theory that the Anti‑Masonic Party was established.

Although there has never been any evidence that the Masonic fraternity had anything to do with the disappearance, the event created great excitement, and led many to believe that several members of the Masonic fraternity were responsible for the disappearance and that, ultimately, Masonry and good citizenship were incompatible. DeWitt Clinton, Governor of New York and himself a Mason, offered up a reward of $1,000 for the apprehension of the guilty person or persons.

Thurlow Weed, a political opponent of Governor Clinton with an unsavory reputation, Thaddeus Stevens (a well‑known future Congressman), Millard Fillmore (a future Presidential candidate), William Seward (future Governor of the State of New York and then Secretary of State for the Lincoln Cabinet) and former President John Quincy Adams set out to stir up the opposition to the Masonic fraternity for political reasons; however, it was the unscrupulous and manipulative tactics of Thurlow Weed that spearheaded the movement by charging the Fraternity with felonious actions to such a degree that Morgan’s disappearance became a national issue. Opposition to Masonry was taken up by the churches as a sort of religious crusade, and it also became a political issue in western New York, where Weed had the unrecognizably decomposed body of a man who washed up on a beach forty miles from Niagra declared, by a coroner’s inquest, to be that of William Morgan, despite the fact that Morgan’s wife could not identify or see any resemblance to her husband. With this act, more than a year after the incident, and the creation of nauseating publicity on the subject for political purposes, Weed was able to cause the citizens in many mass meetings to resolve to support no Mason for public office.

One great factor which tended to keep this excitement alive was the influence of politicians, who sought to use this as a lever to lift themselves into power. The Presidential elections were approaching, and all manner of stories were put into circulation and printed by the anti‑Masonic papers, the most notable among them was the Albany Evening Journal, under the editorial management of, whom else, Thurlow Weed, now a member of the State Legislature.

As an illustration of the sentiment of the times, here is a reprint from Weed’s Journal: “Freemasonry is the step that leads down to the dark gates of hell – the paths of perdition – conclaves of corruption and licentiousness – protection of fraud and villainy – the genuine academies of tippling – manufacturers of noodles…”3 Is there any wonder why the anti‑Masonic movement became so popular among the devoutly religious society of the day?

In New York, at this time, the National Republicans were a very feeble organization, and shrewd political leaders, like Weed, at once determined to utilize the strong anti‑Masonic feeling in creating a new and vigorous party to oppose the rising Jacksonian Democracy. In this effort they were aided by the fact that Andrew Jackson was a prominent Mason and frequently spoke in praise of the Order.

In the elections of 1828, the new party proved unexpectedly strong, winning several seats in State Legislatures of New York, Pennsylvania and Vermont, and after this year it practically superseded the National Republican party in New York. In 1829 the hand of its leaders was shown, when, in addition to its antagonism to the Masonic Fraternity, it became a champion of internal improvements and of the protective tariff.

From New York, the movement spread into other Middle Atlantic states and into New England, becoming especially strong in Pennsylvania and Vermont.

A national organization was planned as early as 1827, when New York leaders attempted, unsuccessfully, to persuade Henry Clay, though a Mason, to renounce the Order and head the movement.

In September of 1831, the party, at a national convention in Baltimore, nominated, as its candidate for the Presidency, William Wirt of Maryland; and in the election of the following year, the party secured all seven of the electoral votes of the state of Vermont. This was the high tide of its prosperity.

The party quickly began to lose its vigor in New York in 1833, and its members gradually united with other opponents of Jacksonian Democracy in forming the Whig party, which was actually able to elect two men to the Presidency. In other states, however, the anti‑Masonic party survived somewhat longer, but by 1836, most of its members had united with the Whigs. Its last act in national politics was to nominate William Henry Harrison for President and John Tyler for Vice President at a convention in Philadelphia in November of 1838; however, the party completely disappeared, the remnants converging with the Whig party who adopted the anti‑Masonic Presidential candidate as their own and won the election.

This country has seen fierce and bitter political contests, but no other has approached in intensity those of the anti‑Masonic times. None but those who witnessed it can justly appreciate the condition of things at that time, and to what extent feeling was carried. One writer describes it as “that fearful excitement which swept over our land like a moral pestilence; which confounded the innocent with the guilty; which entered even the Temple of God; which distracted and divided churches; which sundered the nearest ties of social life; which set father against son and son against father; arrayed the wife against her own husband; and, in short, wherever its baleful influences were most felt, deprived men of all those comforts and enjoyments which render life to us a blessing.”4

The growth of the anti‑Masonic movement was due to the political and social conditions of the time rather than to the Morgan episode, which was merely the torch that ignited the conflagration. Under the name of “Anti‑Masons,” able leaders united those who were discontented with existing political conditions; and the fact that William Wirt, their choice for the Presidency in 1832, was not only a Mason, but even defended the Order in a speech before the convention that nominated him, indicates that simple opposition to Masonry soon became a minor factor in holding together the various elements of which the party was composed.

1 Campbell‑Everden, William Preston. Freemasonry and its Etiquette. New York: Crown, 1978; pg. 11.

2 Stillson, Henry Leonard. History of the Ancient and Honorable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons, and Concordant Orders. London: Fraternity Press, 1892; pg. 508.

3 McCarthy, Charles. “The Antimasonic Party: A Study of Political Anti‑Masonry in the United States, 1827‑1840,” Report of the American Historical Association for 1902. Washington: Hammond, 1903; pg. 217.

4 Mackey, Albert G. and W.R. Singleton. The History of Freemasonry, vol. VI. New York: Fraternity Press, 1898; pg. 368.

by Shawn Donohugh

The author is a Past Master of Moneta Lodge No. 405 (now Gardena-Moneta Lodge No. 372) and a four-time Past Master of Los Angeles Harbor Lodge No. 332. He currently serves as the Secretary of Los Angeles Harbor Lodge No. 332, Secretary of the Southern California Past Master’s Association, is a member of the Grand Lodge of California’s Lodge Support Committee, and served as Senior Grand Deacon for the Grand Lodge of California in 2014-2015.

Thurlow Weed

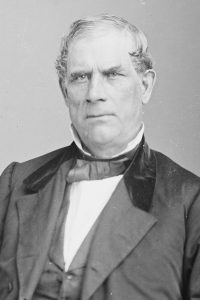

DeWitt Clinton

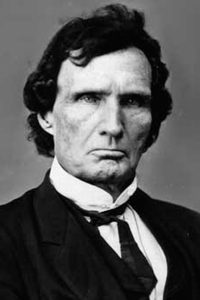

Thaddeus Stevens

Millard Fillmore

William Seward