Some places can only be visited with our eyes closed.

Imagine it is Saturday, November 4, 1752. We are standing outside John Jones’s Tavern on Caroline Street in Fredericksburg, Colony of Virginia. Wisps of smoke drift up from several of the tavern’s chimneys. Perhaps overhead a thin sliver of moon illuminates the night, casting a pale glow over the town, or maybe there are rain showers. John Jones’s tavern is a wooden structure, probably two stories, and typical for its day. Yet in 1752, a tavern is more than just a gathering place for locals to tell a few tales and drink a mug or three of ale-the ale is particularly potent, at about 7% alcohol. Taverns of the colonial era (there are sever al on Caroline Street alone) are not what we think of as a tavern today. In the colonial period, taverns also serve as landmarks-beacons in the night for travelers to inquire of directions to the next town, find shelter, or have a hearty meal. Emulating their European counterparts, taverns act as drop spots for mail and distribution points for news drifting in from the other colonies. Most importantly, especially for the future United States, the tavern is a meeting place where rebels and loyalists alike can discuss new ideas and engage in the debates of the day. Imagine, then, a colonial tavern as a cross between a hostel and a com- munity center that serves beer.

John Jones’s tavern smells of strong hops, candle wax, burnt whale oil, cooked food, and men. The ale is cold because it is November, and the barrels are stored in unheated rooms.

A gentleman enters. He is a tall fellow-a hand higher than most of the other patrons. He has traveled from his home in Ferry Farm, just across the Rappahannock River from Fredericksburg. He has business here tonight, for he has come to knock on a door.

John Jones’s tavern is also the meeting place of the Lodge of Fredericksburg. There is no lodge number, although it would become Fredericksburg Masonic Lodge No. 4 when they began numbering Masonic lodges in the Virginia after the War of Independence. Regardless, the Lodge has business tonight. They are initiating a new candidate.

Were there patrons still inside when the initiation took place? Was the poor blind candidate accompanied by friends and cheerfully greeted upon entering, or was he alone and met with the cold, indifferent stares of strangers? This detail is lost to history. Did the Lodge meet in the main room? Was the Tyler literally standing outside the front door of Caroline Street, or did the Masonic Initiation take place in the ack room or on the second floor? Was the ritual even something we would recognize Masonic ritual today? This is difficult to say, as ritual standardization would not occur for another twenty years, with the publication of William Preston’s Illustrations of Masonry (1772). There is, however, a door – and there is most certainly a knock.

The gentleman is asked three questions, which he must and does answer in the affirmative. A report is made to the Worshipful Master. The Worshipful Master makes the following announcement. It is probably not word for word, but Preston’s 1772 monitor is a good guide.1

“At the request of Mr. George Washington, a planter from King George County,2 I propose him in form as a proper candidate for the mysteries of Masonry; I recommend him, as worthy to share the privileges of the Fraternity; and, in consequence of a Declaration of his intentions, voluntarily made and properly attested, I believe he will strictly conform to the rules of the Order.”

It is hard to imagine that no one in the room bats an eye at the name George Washington. No eyebrows are raised; no chins are scratched; no images of half-finished portraits, cutting down of cherry trees, or the famous face staring out from the one-dollar bill come to mind. The name does not resonate with the immense historical legacy it one day will command. At this moment, he is only George Washington, a twenty-year-old3 gentleman from a prosperous Virginia family. His initiation tonight is a rite of passage, almost a responsibility for him. Tonight he takes his first step in Freemasonry. He is Brother George Washington, the youngest Entered Apprentice at the Lodge at Fredericksburg.

These images can still be sensed on visiting the Fredericksburg Lodge and its surrounding streets in Fredericksburg, Virginia, today, but one can close one’s eyes anywhere and travel to that special place and time through the mind’s eye.

ENDNOTES

1 The wording in the announcement used in this reconstruction of the event is from William Preston’s Illustrations of Masonry (1772) .

2 Washington also may have been announced as being from Ferry Farm or even Fredericksburg and his occupation as a farmer.

3 George Washington was actually 21 when he was initiated into Freemasonry. England had just switched to the Gregorian calendar two months earlier on September 2, 1752, and the news probably had not reached Fredericksburg yet. That would actually push Brother Washington’s initiation to Wednesday, November 15.

by M. Christopher Lee

The author is a member of the Scottish Rite from Kansas City, Missouri

Reprinted by kind permission from the Scottish Rite Journal

Tavern on Caroline Street: Fredericksburg Lodge met at the Rising Sun Tavern in Fredericksburg, Virginia, from 1814-1816.

Photography: Cordelia Dreisonstok

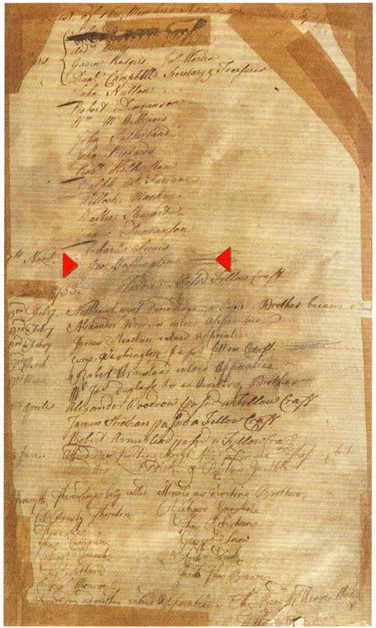

George Washington’s signature, having just received his Fellowcraft Degree in Fredericksburg (indicated by arrows)

Photography: Cordelia Dreisonstok

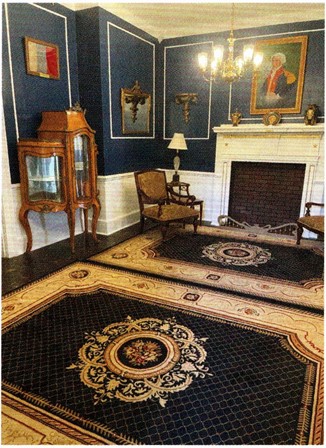

In an Eighteenth-century Drawing Room: A recreation of a Louis XVI style drawing room at Fredericksburg Lodge. The Marquis de Lafayette was made an honorary member in the current building’s Old Lodge Room on Princess Anne Street in 1824.

Photography: Cordelia Dreisonstok