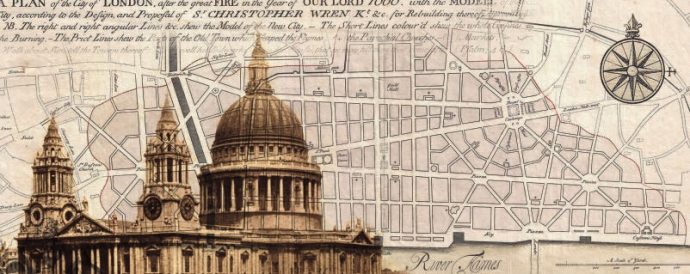

The architectural renaissance in London after the Great Fire is a credit to the vision and legacy of Sir Christopher Wren.

Early on a Sunday morning, Sept. 2, 1666, a fire broke out in a bakery in Pudding Lane, in the center of London. By Sunday evening winds had created an inferno which destroyed most of the historic city within the ancient Roman walls, including St. Paul’s Cathedral atop Ludgate Hill. Thousands of homes were destroyed, as well as 87 parish churches, and the British capital was reduced to ruins. By the time the fire had burned itself out on the following Wednesday, the great city was no more. Some 100,000 people were left homeless, and the smoldering ruins prevented a quick return to the houses that remained untouched.

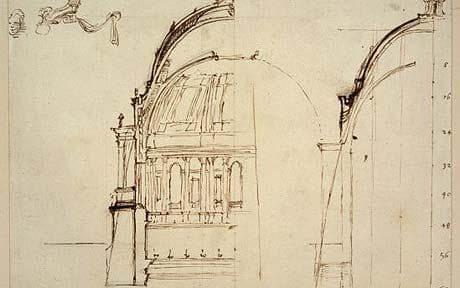

St. Paul’s Cathedral was the most important symbol of the old London, and King Charles II moved immediately to replace the destroyed church to show his commitment to the British capital. The architect Christopher Wren had been retained even before the Great Fire to remodel the old cathedral, and it was natural that he would be given the assignment to build its replacement. The building that arose on the site was truly a monument to the man who was undoubtedly the greatest British architect of his day. In the month of June, 1675, the first stone of the new cathedral was laid by the stonemasons of London under the direction of Thomas Strong, one of the two Master Masons that Wren appointed to oversee the construction. There is no evidence that these two Masons belonged to the Masonic lodge which met at the Goose and Gridiron Tavern across the square from the cathedral site, but it is possible that they were members. We know that this lodge was a “time immemorial lodge,” and one of the four lodges which founded the first grand lodge in 1717. The lodge is still in existence, with the name and number of “The Lodge of Antiquity No. 2” on the rolls of the United Grand Lodge of England.

The new cathedral was built of Portland stone in a late renaissance style, which was Wren’s version of English Baroque. The structure is a tribute to his understanding of the beauty and harmony of classical architecture melded with the historic cruciform style of ancient cathedrals. The building was declared complete by Parliament on Christmas Day, 1711. It was Wren’s masterpiece – the culmination of his life as an architect – and he is thus considered to be one of the most acclaimed architects in English history. In addition to St. Paul’s Cathedral, he built fifty-two more churches in London after the Great Fire, as well as some secular buildings of note.

In keeping with his time, Wren came to the study of architecture from the study of the liberal arts and sciences, especially astronomy, mathematics and geometry. He was a founder of the Royal Society, the world’s first scientific organization, which at his death in 1723 included many of the most famous names in the world of science and mathematics. He was knighted by the king on Nov. 14, 1673, and thus is known to history as Sir Christopher Wren.

There is no evidence that Wren was a Freemason, although in 1738 the premier grand lodge claimed that he was. In fact the Constitutions of 1738 explicitly stated that his “neglect” of the craft as “grand master” due to his advancing years was responsible for the decision in 1717 to form the world’s first grand lodge. We may never know for sure if England’s most celebrated architect was a Mason, but the monument that he left in the magnificent cathedral in the heart of London is truly a tribute to the builder’s art. He certainly associated with prominent Freemasons such as John Desaguliers, who was grand master in 1719, and who was also secretary to the Royal Society when Wren was a member.

At his death he was buried in the cathedral which was his greatest achievement, and this inscription was carved on his tomb:

SUBTUS CONDITUR HUIUS ECCLESIÆ ET VRBIS CONDITOR CHRISTOPHORUS WREN, QUI VIXIT ANNOS ULTRA NONAGINTA, NON SIBI SED BONO PUBLICO. LECTOR SI MONUMENTUM REQUIRIS CIRCUMSPICE Obijt XXV Feb: An°: MDCCXXIII Æt: XCI.

In English it reads:

“Here in its foundations lies the architect of this church and city, Christopher Wren, who lived beyond 90 years, not for his own profit but for the public good. Reader, if you seek his monument–look around you. Died 25 Feb. 1723, age 91.”

Whether or not Sir Christopher Wren was a Freemason as alleged by the Grand Lodge in 1738, no greater tribute to any Mason could be given than this. The lives that we lead, “not for [our] own profit but for the public good…..” are the best and most lasting monument to our work as Freemasons. At the end of our earthly journey what we did in life will be a far greater monument than any of marble or brass. It may well be said of each of us when we lay down our working tools, “Reader, if you seek his monument – look around.”

by John L. Cooper, III

Reprinted by kind permission from the Grand Lodge of California’s “California Freemason.”

The author is a Past Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of California and served 17 years as Grand Secretary. Most Worshipful Cooper is a Past Master of the James A. Foshay Lodge No. 641 (now Culver City-Foshay Lodge No. 467), Southern California Research Lodge No. 1005, and the Northern California Research Lodge No. 1003. He has served on several Grand Lodge boards and committees, including the Masonic Homes of California, California Masonic Memorial Temple, Masonic Formation, and Masonic Education. He holds the Chevalier Degree and the Active DeMolay Legion of Honor, and is an honorary member of the International Supreme Council. Interest in the historical aspects of Freemasonry led Cooper to the York and Scottish Rites, where he has received the Knight of the York Cross of Honor, the Distinguished Service Medal in Silver from the General Grand Chapter of Royal Arch Masons, the rank of Knight Commander of the Temple in the Grand Encampment of Knights Templar and the Inspector-General Honorary of the 33rd degree of the Scottish Rite.